Debugging Your Brain Part 2, Breakpoints

This post was a precursor

to Casey's book

"Debugging Your Brain."

CBT, Introspection, and Inputs

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Introduction to CBT

Do you want to be a happier and more effective person? Let’s try Cognitive Behavioral Therapy!

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a specific and common form of “talk therapy”. CBT is effective for depression, anxiety, general stress from work, and much more!

The core idea is that certain thought patterns contribute to emotional distress and behavioral issues. These “cognitive distortions” offer an inaccurate view of the world and/or yourself, and they can be changed and improved with practice and effort. The term “cognitive distortions” is usually used interchangeably with “maladaptive thought patterns” and “maladaptive cognitions”.

The full list of mental problems CBT can help with is quite long - more than fifteen! Here’s one source that lists a bunch of them: Hofmann, 2012. I’m not suggesting CBT is necessarily the best or only therapy for every single one of these mental problems. It is, however, one of the top most frequently used techniques, and it’s often very effective.

You may be wondering “Do I need to have a mental illness for CBT to help me?” Nope! The use of the word “therapy” might lead you to believe that CBT only helps if you have a mental illness, but really it’s useful for anybody.

Therapy? Training!

I think of CBT more like “brain training”. To reduce its association with therapy, I like to replace the word “therapy” with the word “training”. A lot of people I know like calling it “Cognitive Behavioral Training” because they find it more approachable. I’m glad the stigma around the word therapy seems to be reducing over time, but the stigma is certainly still around. Mental illness or not, it’s definitely helpful to understand how to process your thoughts and feelings better.

If you are at all unsure whether you would benefit from (“need”) actual therapy, I recommend you see someone to be screened. Please don’t treat this book as therapy — this is not a suitable replacement for the real thing.

More about CBT

This book applies “systems thinking” (like the IPO model) to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. If you’re interested in digging deeper into CBT after reading this book, I suggest the book “Feeling Good” by David Burns. In one study, “Feeling Good” was the most commonly prescribed reading assignment from therapists doing CBT with their patients. In another study, it was found to be as effective as actual therapy for some people.

Positive Outcomes

In my mind, there are two tangible positive outcomes from processing experiences: learning, and reducing involuntary and unwelcome thoughts (“intrusive thoughts”).

If you can learn something from a situation, that might help you in a future similar situation. By “learn” I mean either something specific like “always make sure you have your keys when you leave the house”, or something abstract like “try slowing down and be more careful”.

Processing can also help reduce intrusive thoughts. Imagine a job interview. After the interview you’re not sure how it went, and you think about it a lot. You play back what everyone said and did, thinking about what you could have done differently. This is probably some amount helpful, and some amount unhelpful. If these thoughts continue happening to you at inappropriate times, you might consider them “intrusive thoughts”.

How can you put unwanted thoughts to rest? For a particular experience, try to find value in it by learning something. If you’re not sure there’s anything further you can learn from it, it may help to try accepting it Wells 2014. Finding value or finding acceptance can help reduce the frequency of the intrusive thoughts.

In software terms, intrusive thoughts are a bit like metrics and alerting. The subconscious mind sets up these alerts for itself. It decides that some experiences are important to process, and alerts you of those until they are fully processed. Addressing the root issue can often make it so the alert isn’t fired off as often, or at all.

Hitting Your Debugger

When can you process an experience? It could be during, immediately after, hours after, weeks after, or even years after. How do we get into in introspective state to do this processing (debugging)? It depends on whether you’re debugging during or after the stressful situation. Each is valuable in its own way.

During

If you’re able to debug your brain during a stressful situation, you may be able to change the outcome of that situation. You may also be able to make this current experience a less stressful one.

Many people find it difficult to realize when it’s a good opportunity to introspect in-moment. We’ll go through a technique in the next section to help with noticing opportunities for introspection and getting you into that introspective mindset.

After

When you debug your brain after an experience, you may learn things that can help you in a similar situation in the future. This post-processing can also help reduce how often you think of the situation, and how stressful it is to think about.

The Whoop Technique

A Ripe Situation

To start up your debugger in the moment, I recommend the “whoop” technique.

One day, my mother snapped at my younger brother for leaving the door open. Immediately after, she felt bad and apologized. She told us she really didn’t know why she yelled about “such a small thing”. After thinking about it for a bit, she realized that she hadn’t eaten yet that day and was pretty hungry. That hunger affected both her mood and her response to my brother. After she ate some food, she felt much less irritable. I’m really proud of her going through this whole thought process — great job, mom!

Whoop!

This wasn’t the first or last time this sort of thing would happen. My mom wanted to get better at this — better at noticing things like how her hunger, thoughts, and emotions can affect her mood. Once she got into that introspective state she could figure it out well enough, but she had trouble getting into that introspective state in the first place. In programming terms, she had trouble hitting a “debugger breakpoint”.

My mom asked us to help her next time she got frustrated or upset like this. We brainstormed, and decided that next time we could loudly yell “WHOOP!”. After the whoop, she might enter an introspective state (the “whoop state”) and try processing the experience. Or, she could say “not now” and we would move on. She whoops herself, I whoop myself, my brother whoops himself. We all whoop!

Hopefully this story makes the whoop technique memorable for you. Yelling whoop is both helpful and hilarious. A whoop surprises you out of your current mindset. If you were about to downward spiral, it halts that for a moment. It puts you into a different mental state where you can be ready to think about what made you so frustrated in the first place. For my mom, it wasn’t really what my brother was doing — she figured out it was more about her hunger. We’ll cover more things that might affect your mood later in this chapter.

This technique is most useful for whooping yourself: either out loud, or quietly in your head. If you want to recruit friends or family to support you that’s great, but definitely optional.

In programming terms, a “whoop” is like hitting the “debugger breakpoint” where you can take a moment to “inspect” what’s going on. From here you can inspect local variables, global variables, the call stack, and even run some code that will affect the program even after you leave the breakpoint.

Whoop Practice

It takes a lot of practice to get good at noticing when introspection will help. Just being able to notice opportunities is a huge step forward. Whenever you get into this introspective state (“whoop state”) I want you to congratulate yourself. You’ll get better and better the more you do this. Be patient with yourself in the meantime.

When not to control your thoughts?

It does cost time and energy to introspect. If you don’t have the time or energy to do it as much as you’d like, that’s okay and normal. In fact, sometimes you may enter the “whoop” state briefly, decide it’s not worth introspecting right now, and leave before processing things. If that feels right, that’s totally okay.

You probably want to prevent most downward spirals. Any that are a waste of your time and energy, or if you think you’ll regret your actions. But sometimes it might be worth it to let yourself get worked up — you might be driven to focus on something you wouldn’t otherwise.

I got really upset once. I was eating in a food court, charging my phone, and a security officer rudely told me I couldn’t use the power outlet. I felt myself getting worked up, I whooped internally, and I entered an introspective state. I considered — should I control my thoughts and feelings and prevent myself from being worked up? In this case, I decided to allow this to motivate me to act.

I was energized enough to talk to the manager later and make my thoughts known. I explained: it cost virtually nothing to the company (literally less than $0.001 for a full phone charge). I wasn’t in the way of anything. I wasn’t taking up needed space (the food court was empty). There was no sign up about this rule anywhere. And the person asking me to unplug was rude about it.

If you wouldn’t have acted the same way as me, that’s okay. I believe it was worth it communicating this to the manager, both for the situation and for myself. I felt better because the information (my frustration/rationale) made it to the right person who could potentially change things. I was ready to accept it if they chose not to act on this — but not sharing this information would have bothered me.

You can get very skilled at introspection and still allow yourself to get worked up sometimes. You don’t need to always mechanically control your thoughts.

Let’s imagine that you’re now an expert at using the whoop technique to get into an introspective state. What’s next?

Post-hoc Rationalization

When my brother didn’t close the door, my mom stopped to introspect for a moment. If she hadn’t, she might have might have explained her behavior in an unsatisfying, inaccurate way called a “post-hoc rationalization”. Some blatant examples: “he always does that!” (even if he hasn’t done it much) or “he’s going to let all the heat out!” (even if the heat wasn’t on). Post-hoc rationalization can happen during stressful or non-stressful situations — anytime.

Post-hoc means “after the fact”. We often experience a gut reaction first (inner brain), and then afterwards attempt to explain our thoughts and feelings quickly (outer brain). Often the quick attempt at explaining it is inaccurate or incomplete. This could cause internal conflict for yourself, or conflict with others.

When you find yourself experiencing this, consider taking a moment to introspect. Just because the explanation is inaccurate doesn’t mean the gut reaction isn’t based on something real. By spending time processing you may be able to come up with a fuller, more satisfying explanation for yourself and for others. Whoop!

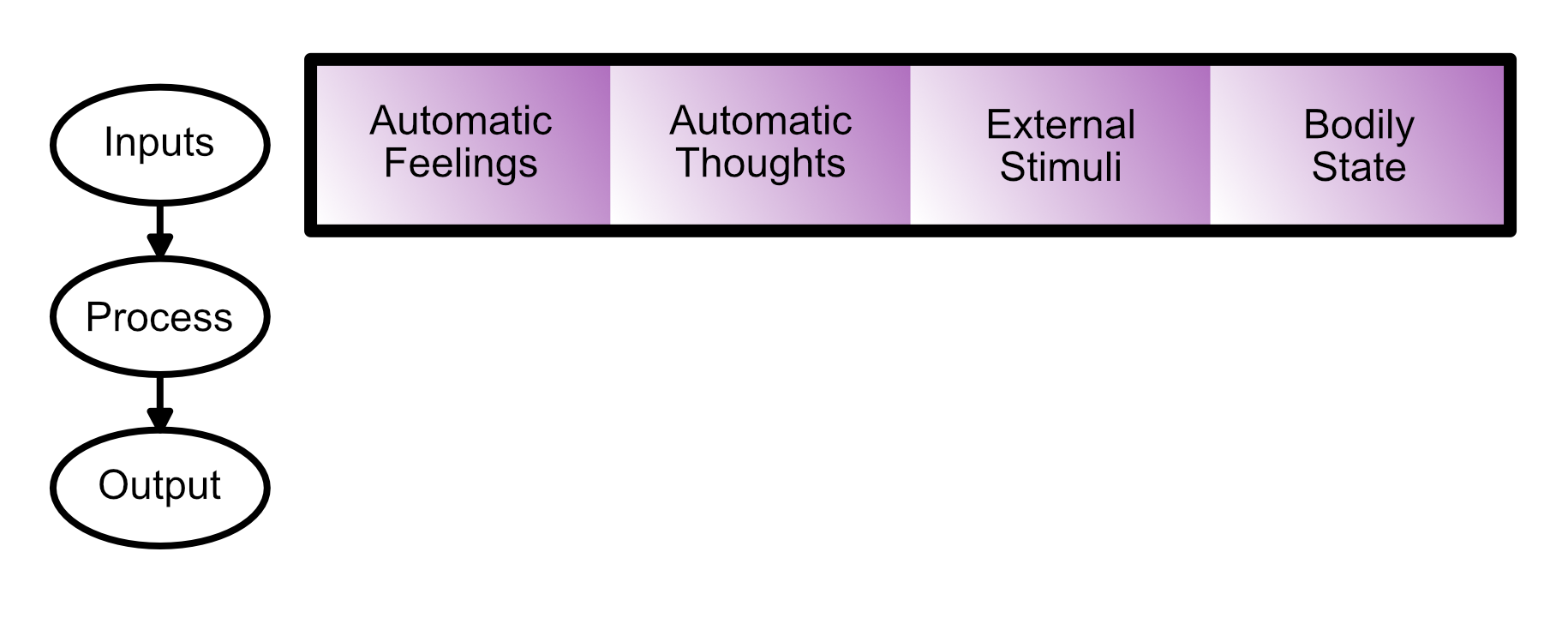

Identifying Inputs

We’ll go through our the Input-Process-Output (IPO) model of the brain in chunks. The first section will be about inputs in general, the next section will go in-depth about processing feelings, and the final section will go in-depth about processing thoughts. Once you process everything, you’ll be well-equipped to choose the most adaptive response.

Let’s talk about the inputs to your system. I break this into four categories: automatic feelings, automatic thoughts, external stimuli, and your current bodily state.

Automatic Feelings

Any feelings you experience are a type of input. A feeling can be present whether you can accurately describe it in words or not. A feeling can sometimes come with automatic thoughts describing it, but sometimes it won’t.

This might encompass a feeling you get in a particular moment like a moment of fear, or a low-level background feeling like being anxious for a day. The specific distinction between these two isn’t super important — it’s more important that you scan yourself for both kinds.

Automatic Thoughts

An automatic thought is one you don’t actively choose to think. In your conscious mind you just “hear” yourself thinking them. My mom automatically thought the words “Oh Dalton, not again!!“. This thought came to her around the same time as an “automatic feeling” of frustration. Both automatic feelings and automatic thoughts are inputs to the conscious part of your brain; these aren’t directly under your control.

External Stimuli

External stimuli are anything that happens outside of your body or mind. Events that happen around you — like my younger brother not shutting the door. It could be some event from earlier in the day, like if you wake up late or miss a cup of coffee. It could be something someone said to you the day, month, or year before. These events happening to you are separate from any thoughts or feelings you have about these “stimuli”.

Bodily State

A fourth type of input is your current bodily state. My favorite example is the word “hangry” — short for hungry-angry (a portmanteau!). If you’re hangry, that means your state of hunger is leading you to experience anger, and you may respond to the situation with anger. When my mom realized she hadn’t eaten, she apologized to my brother, moved on, and got some food.

I am so glad “hangry” has become such a common term. I would love to have an even richer vocabulary like this. I haven’t come up with any mashup words that are quite as catchy as “hangry”, but hyphenation helps me a lot. Instead of pushing for “tiredrated” I just use tired-frustrated instead. Any combination [bodily-state]-[emotional-state] is a possibility. For myself, I distinguish between many types of hungry (stomach-volume-hungry vs sugar-hungry vs thirsty-hungry and more). I distinguish between many types of tired (physically tired vs sleepy-tired vs socially drained vs focused-for-too-long drained).

Those are four types of input: automatic feelings, automatic thoughts, stimuli from the environment, and current bodily state. Now equipped with all this context, we’re ready to start processing these emotions and thoughts.

Homework

- What are the four major types of inputs to your consciousness?

- Practice the “whoop” — whoop yourself 3 times today. While in this introspective state, notice your inputs. Identify inputs from each of the four major types of inputs.

- Explain CBT (at a high level) to a friend. Do a bit of independent research (googling!) if you want to be able to speak about it more accurately.

- Use the term “post-hoc rationalization” in a conversation this week.

Read More

“Debugging Your Brain” is a 5-part series.

- ”Part 1: Modeling” - When brain-debugging helps, and a model of how the brain works when debugging.

- ”Part 2: Breakpoints” - How to get your mind into a state where you can debug: how to hit a breakpoint. Here you’ll investigate what the “inputs” to your system are.

- ”Part 3: Processing Experiences” - Six concrete ways to deal with processing experiences more fully and effectively.

- ”Part 4: Validation and Close Relationships” - How to effectively validate and support close friends.

- ”Part 5: Thoughts” - You’ll learn about the 10 most common “maladaptive thought patterns” you’ll want to look out for and convert into “adaptive” thought patterns.